Copyright

2014 by Gary L. Pullman

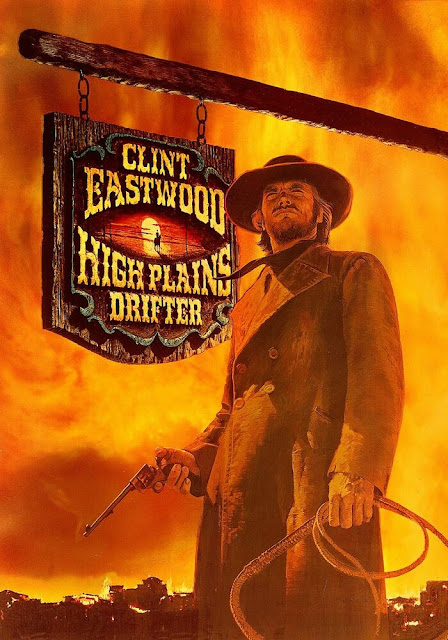

Although it's not unusual

for Western movies (and books) to express religious themes, such

dramas and narratives rarely have supernatural elements. Two

exceptions to the “rule” are Clint Eastwood's films High

Plains Drifter (1973) and Pale

Rider (1985).

In the

former picture, certain of the protagonist's characteristics and

abilities suggest that there may be more to him than is first

apparent, and the movie provides a clue or two as to the possible

nature of the stranger.

First,

as James L. Neibaur points out in his chapter “High Plains Drifter”

in The Clint Eastwood Westerns,

the “stranger” whom Eastwood plays “is mysterious, he is

controlling, he is all-knowing, and he is powerful” (104).

Second,

Sarah Belding, the wife of hotel operator Lewis Belding, tells the

stranger that the town's previous sheriff, Jim Duncan, was buried in

an unmarked grave, adding “the dead don't rest without a marker”

(104).

Third,

in a dream it is revealed to the stranger that the town's leaders

conspired to have the sheriff beaten to death by three brothers with

whips, before allowing the murderers to be arrested. Having been

released from prison, the killers are now on their way back to the

town, Lago, to avenge themselves on the town.

Fourth,

after painting the town red and renaming Lago “Hell,” the

stranger abandons the townspeople, just as the killers return. In his

absence, many of the citizens are killed, and the town itself is

burned to the ground. It is only then that the stranger returns and

kills one of the murderers, Dan Carlin, using a whip, which he

then throws into the saloon, “alerting the two surviving brothers,”

whom he kills (104).

Fifth,

as the stranger rides out of Hell, Mordecai, a dwarf whom the

stranger had named mayor and sheriff of Lago, is in the town's

cemetery, carving a marker for a grave. “I never knew your name,”

Mordecai says. “Yes, you do,” the stranger replies. The marker

Mordecai carves bears the name Marshal Jim Duncan; it is for the

sheriff's once-unmarked grave. Presumably, now that his grave is

marked, the stranger will be able to “rest.”

As

Neibuar observes, There has been some discussion as to the identity

of the stranger”:

The script originally indicated that the stranger was

the marshal's brother . . . and the scenes alluding to this

[identity] were filmed, but Eastwood had them excised. In the film,

the stranger is more a ghostly figure, perhaps a reincarnation of

Duncan, based on the final lines between him and Mordecai and the

supernatural air of the story” (107-108).

The New York Times's

1973 review of the film also suggests that the movie is intended to

have a supernatural angle:

High

Plains Drifter, with Eastwood as

director as well as star, is part ghost story, part revenge Western .

. . . It exalts and delights in a kind of pitiless Old Testament

wrath . . . Eastwood's characterization of The Stranger [is that of a

figure] who settles God's score with Lago . . . (108).

The

fact that Eastwood, the director, cut the scenes that represents the

stranger as the sheriff's brother and the clues that the character is

a ghostly or reincarnated avenger, seem clearly to suggest that

Eastwood himself wants the movie to be understood as having a supernatural theme.

Twelve

years later, Eastwood would make another Western with a supernatural

slant, Pale Rider

(1985). Like the ghostly stranger in High Plains Drifter,

The Preacher of Pale Rider

“is mysterious, he is controlling, he is all-knowing, and he is

powerful,” or, as Neibaur describes him, “he seems to have a

mysterious, mystical quality, able to evade people in a gunfight by

seeming to disappear. He comes from nowhere; he leaves when the job

is done” (149).

The

Preacher's association with Christianity is made plain by his

arrival, just as fourteen-year-old Megan Wheeler is praying that God

will send someone to deliver her mother, herself, and the other gold

prospectors from the gunmen who just stormed through and destroyed

their camp, killing her dog.

When

she sees The Preacher riding into the ruins of the prospectors' camp,

Megan believes that he is the answer to her prayer, and, indeed, he

rides a pale horse, just like one of the four horsemen of the

apocalypse, of whom she has just read in the book of Revelation: “And

I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was

Death, and Hell followed with him.”

In

discussing The Preacher, the Chicago Tribune's

editorial writer, Stephen Chapman points out that he is not Christ

the Savior, but the Jesus “who brought not peace but a sword, the

one of Revelation who raises the righteous into heaven and casts the

wicked into the depths” (149).

The

Preacher's supernatural origin is also suggested by the feats he

accomplishes single-handedly, exploits that the men among the

prospectors are unable to accomplish collectively. He fights off

several men, defeating them with no other weapon than an axe handle;

he defeats a Goliath-size adversary with the same sledgehammer he

uses to cleave a boulder in half with a single blow; he outguns a

group of gunfighters notorious for their skills with a pistol; when

he departs, he leaves behind him a courageous and united community

who, before his arrival, were divided and afraid.

As

Neibaur suggests, Eastwood underscores the supernatural dynamics of

Pale Rider by ensuring

that it shares similarities with his other supernatural film, High

Plains Drifter:

The

setup [of Pale Rider]

has immediate similarities to High Plains Drifter

(1973) upon the Eastwood character's entrance. In that film [High

Plains Drifter], he enters a

very quiet town. In Pale Rider,

he arrives as the town has quieted down from a most recent attack.

Among the first things the stranger does in High Plains

Drifter is respond with stoicism

to men confronting him in a saloon, later shooting them down when

they physically accost him in a barber shop soon afterward. In Pale

Rider, the stranger comes to the

rescue of a man being attacked by a group of others, effectively

beating them down. . . . The man he rescues, Hull Barrett . . . the

leader of the miners, invites the stranger to his house for dinner.

He appears wearing a clerical collar and is thereafter referred to as

The Preacher. These initial scenes establish the character's

abilities as well as a mystery about his backstory (148).

The

scenes also establish a link between the two supernatural films and

their supernatural heroes. However, the older movie invokes

reincarnation to explain Sheriff Jim Duncan's return from the dead,

while the later film invokes the Bible, solidly grounding Pale

Rider's supernatural aspects in

the Christian vision of death and judgment.

In

High Plains Drifter,

the stranger creates Hell; in Pale Rider,

he is death, delivering the wicked to judgment, for, although Chapman

sees Eastwood's Preacher as Jesus, the movie itself offers several clues that suggest a different identity for The Preacher: the film's very title, which is an allusion to Revelation 6:8, the Bible verse that equates

the “pale rider” to Death, the apocalyptic horseman who ushers in

hell, and the nature of The Preacher as a supernatural figure

delivered by God in answer to Megan's prayer clearly indicate that he

is Death personified, not Jesus.

Whereas

the stranger in High Plains Drifter

abandons “sinners” to hell, The Preacher in Pale Rider

kills the wicked and appears to leave their eternal fate to the

judgment of God.

Supernatural

Westerns are so unusual that their existence—and their raison

d'être—seem

to beg explanation. Despite the mystical undertones of High

Plains Drifter

and the Christian overtones of Pale

Rider, it's

likely that neither film is an expression of religious faith on the

part of Eastwood himself, who told movie critic Gene

Siskel that he is an atheist. However, Eastwood also admitted

that he does “feel spiritual

things,” declaring that “if I stand on the side of the Grand

Canyon and look down, it moves me in some way.” He's also a devoted

practitioner

of Transcendental Meditation.

Eastwood's

own take on his supernatural Westerns is that both are allegories.

High Plains Drifter,

he says, is “just an allegory . . . a speculation on what happens

when they go ahead and kill the sheriff and somebody comes back and

calls the town's conscience to bear.

There's

always retribution for your deeds” (The

Clint Eastwood Westerns,

105). Likewise, Eastwood explains, “Pale

Rider is

kind of allegorical, more in the High

Plains Drifter

mode: like that, though he isn't a reincarnation or anything, but he

does ride a pale horse like the four horsemen of the apocalypse . . .

It's a classic story of the big guys against the little guys . . .

(The Clint Eastwood Westerns,

149).

For

Eastwood, perhaps each of his supernatural movies is “just an

allegory,” but, of course, the creator of a work of art doesn't

determine its meaning, except for himself. Any interpretation that is

supported by the details of the story itself is both reasonable and

possible, and there seems more internal evidence in Pale

Rider for a Christian

interpretation than for an atheistic or a secular one.

After

all, the movie deliberately alludes to Christian beliefs, to a

specific Biblical account of apocalypse and judgment, and to a

supernatural order of existence that transcends the ordinary world of

the Wild West in which the movie is set.

Western

culture is suffused with the traditions of the Christian faith;

allegories which include supernatural characters and events,

especially when they are informed by specifically Christian doctrine

and tradition, can certainly be reckoned to possess and to

communicate Christian themes.

Bane

Messenger, the protagonist of my own series, An Adventure of the Old

West, has a name of religious significance as well. Bane (the

nickname by which Banan goes) derives from the Old English word bana,

meaning “killer, slayer, murderer, a worker of death”; the Late

Latin word angelus means

“messenger.” Putting them

together, Bane Messenger can be read as meaning Angel of Death,

which, the books of the series, Good With a Gun,

The Valley of the Shadow,

and Blood Mountain,

suggest, as does the short story “Bane Messenger, Bounty Hunter,”

a prequel that introduces the series, is how Bane regards himself.

His

skill with a gun, like his indomitable will, his steely nerve, and

his love for justice, equip him as an instrument of divine

righteousness and wrath. It's his mission, he believes, to use the

“gifts” he's received to ensure that justice triumphs and the

innocent are protected from “the worst sort of men,” those, as a

bounty hunter, he tracks down to kill or, as a lawman, risks his life

to stop. Believing himself on a mission sanctioned by his Creator,

Bane puts his own fate in the hands of God every time he draws his

gun, putting his life in mortal danger in order to bring desperate

killers to justice, dead or alive.

No comments:

Post a Comment