Copyright 2020 by Gary L. Pullman

Born

in Oak Hill, Missouri, near St. Louis, a year before the end of the

American Civil War, Charles

M. Russell became an early devotee of the American West, working

first as a shepherd and then as a cowboy on Montana ranches. After

marrying Nancy Cooper, in 1896, Russell began his career as a

full-time artist, “painting and sculpting” inside his “log

cabin studio next to their home” in Great Falls, where he died in

1926, leaving a legacy of work chronicling and commemorating the time

and place he'd loved all the days of his life.

In

over two thousand paintings, Russell captures the spirit

and adventure of the Wild West. His work depicts roundups, bronco

busting, the fording of rivers, cowboys' encounters with wild

animals, buffalo hunts, camping, gambling, scouting, gold mining,

hunting, and much more.

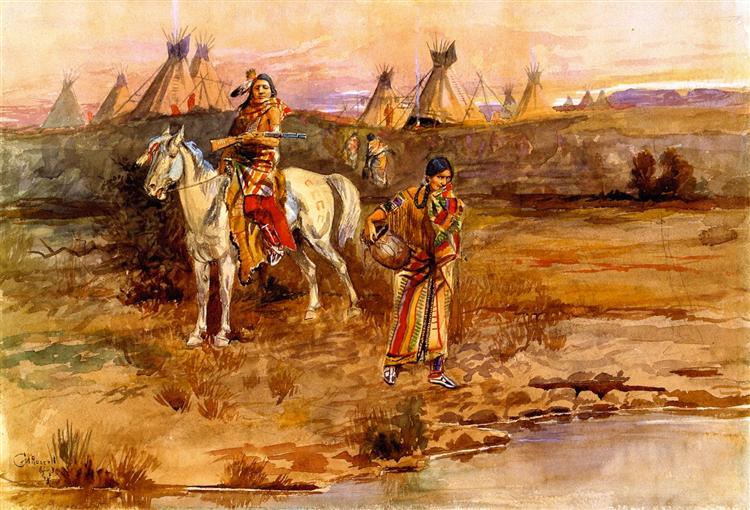

Many

of his paintings are also devoted to the nomadic life of Native

Americans, as they hunt buffalo, fight cavalry soldiers, attack

frontiersmen, travel from campsite to campsite, grieve fallen

warriors, greet the famous explorers Lewis and Clark, encounter other

tribes, worship, communicate by smoke signals, and perform other

tasks of daily life.

Several

tribes are portrayed, including the Piegan, Crow, Sioux, Blackfoot,

Chinook, Navajo, Shoshone, Cree, Mandan, and Kootenai. By today's

standards, Russell's portraits of Native Americans are, at times,

politically incorrect. In his art, which depicts its subjects'

encounters with both other tribes than their own and with white men,

whom they see variously as traders, fighters, settlers, and invaders,

battles, bloodletting, and death are likely to follow.

More

than a few of the paintings are dedicated to displays of Native

Americans at war, both with each other and with whites. as the works'

titles suggest: Scouting the Enemy,

On the Warpath, The

Battle Between the Blackfeet and the Piegans,

War Council, The

Making of a Warrior, Planning

the Attack, The

Attack, Indian War

Party, Sun River War

Party, Battle of Belly

River, Mandan Warrior,

Return of the Warriors,

Cree War Party, The

War Party, and WAR.

When

Native Americans are not waging war, they are often engaged in other

hostile acts, against other tribes or against white men, as they are

in such paintings as Sioux Torturing a Blackfoot Brave,

Planning the Attack on the Wagon Train,

The Horse Thieves,

Blackfeet Burning Crow Buffalo Range,

and Crow Sheep Stealer.

Not

all of Russell's paintings depict Native Americans as uncivilized,

battle-driven killers, thieves, and arsonists, of course. A couple

show individuals as “noble” and “romantic” figures. In a

number of works, Russell's Native American subjects are even

portrayed in a seemingly lighthearted or humorous fashion (A

Piegan Flirtation, Indian

Beauty Parlor, Waiting

and Mad), a reverent manner

(Invocation to the Sun, Sun Worship in Montana),

or a diplomatic pose (Lewis and Clark Meeting

Indians at Ross' Hole, Lewis

and Clark Reach Shoshone Camp Led by Sacajawea the Bird Woman,

Indians Discovering Lewis and Clark,

Lewis and Clark Meeting the Mandan Indians).

One

can't help but to notice, however, that in the diplomatic series

involving the meetings between Lewis and Clark and various tribes,

the white explorers receive top billing in the titles, and it is

usually they, not the Native Americans, who are assigned the active

role; it is they who meet; even when Sacajawea leads, her name

appears after theirs, and they are assigned the primary active role:

they “reach” the Shoshone's camp. It is almost as an afterthought

that their guide's action, in leading them, is mentioned. Clearly, in

Russell's view of the American West, whites are the protagonists. His

Native Americans are the villains or supporting characters or, in

some cases, even window dressing.

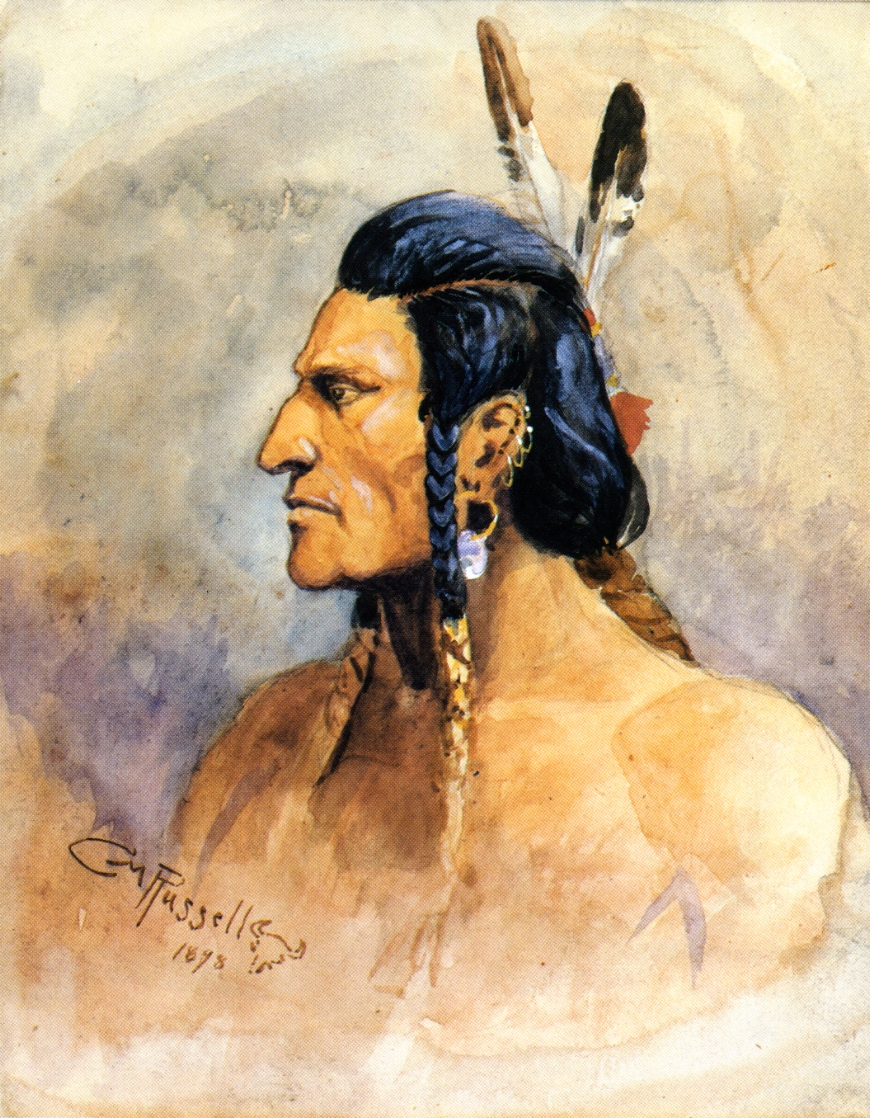

Russell's

work tends to show Native Americans as treacherous and militant or,

in the comparatively rare moments in which they are not burning a

field, torturing an enemy, plotting battles, or waging war, as

comical, paganistic (animistic), or helpful to the active, purposeful

white men they serve. There is only one other major category of

Native American on display in the artist's gallery of “Indians”:

the stereotypical representative, usually in portraiture, of Indian

Brave, Indian Buck,

Indian Squaw, and [Portrait

of an] Indian.

Although

Russell is largely positive in his portrayal of white men as the

heroic tamers of the Wild West, he also lampoons them on occasion and

shows them in a bad light at times. In one painting, a cowboy tries

to “bargain” with a Native Indian “for an Indian girl.”

In

another work, Whooping It Up, a band of cowboys, apparently drunk, gallop down the

main street, past a saloon, shooting their revolvers at the sky and

frightening a Chinese pedestrian, who drops a basket of laundry,

scattering chickens, while a dog runs in the opposite direction and,

across the street, men look on from the boardwalk in front of a

saloon, while Asian women in front of Hop Lee's Laundry stare in

fear. The white men's behavior is reckless and dangerous, but no one

seems ready to intercept or challenge them.

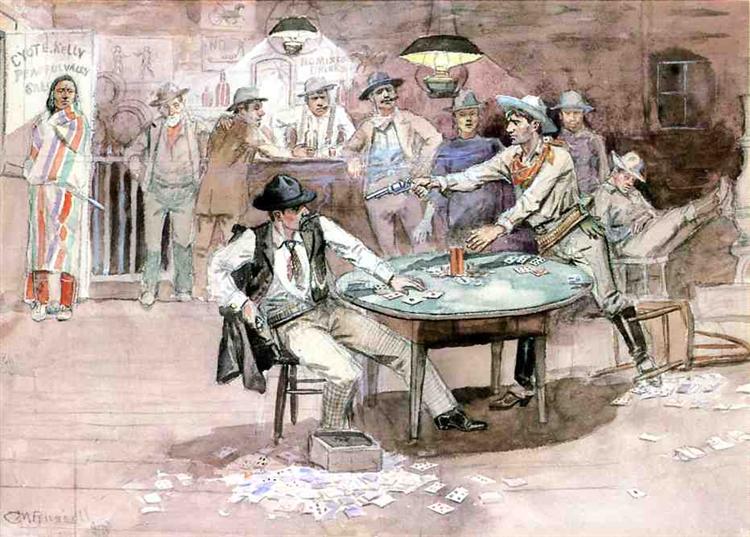

In

the ironically titled Peaceful Valley Saloon, gamblers are

about to duel at their table, possibly to settle a charge of cheating

at cards; one hold his extended weapon, while his adversary begins to

draw his own six-shooter from his holster. None of the other patrons

of the saloon, including the bartender, appears concerned, suggesting

they have seen such behavior before. Adding to the irony is the

Native American who looks on, rifle in hand, a stoic expression on

his face, since, often, in Russell's' work, Native Americans are

depicted as hostile and violent.

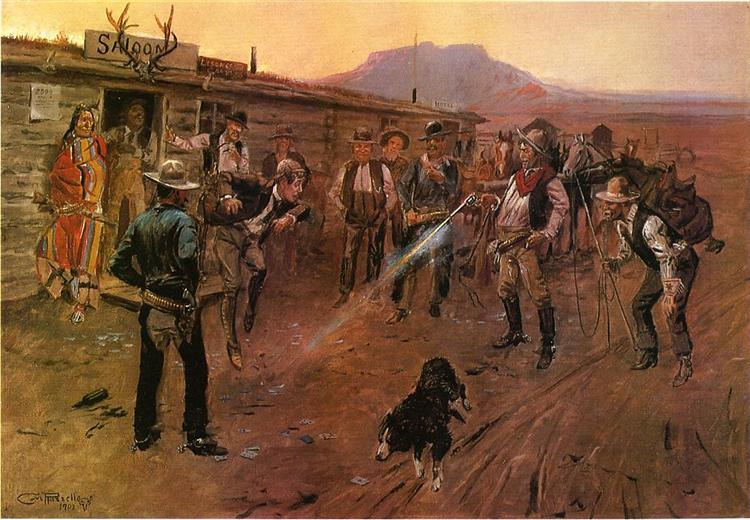

In

The Tenderfoot, a cowboy makes a new arrival to the West, who

is still dressed in the fashion of the East, “dance” by shooting

his pistol at the dude's feet, much to the amusement of the other

frontiersmen gathered outside the saloon before which the spectacle

takes place and to the consternation of a fleeing dog. Even the token

Indian in the group looks amused by the potentially dangerous

shenanigans.

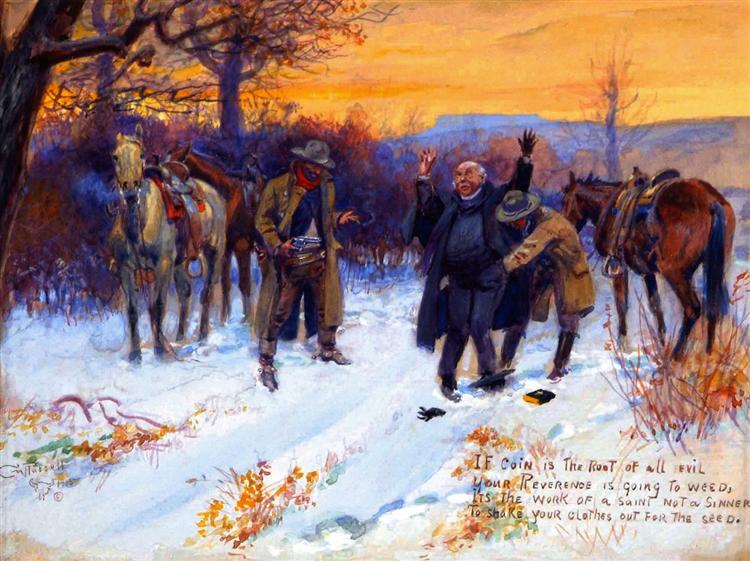

Outlaws,

as such, are fairly rarely represented in Russell's work. However, a

pair of highway robbers appears in Fleecing the Priest, and,

as the painting's title indicates, their victim is a man of the

cloth. As one of the robbers holds a gun on the clergyman, who stands

between the two outlaws, his hands overhead, looking frightened, the

other reaches deep into the left pocket of the unfortunate soul's

trousers. The lining protruding from the other pocket suggests that

it has already been searched. Four lines of partially rhyming verse

explain the villains' attitude toward the man they are robbing:

If coin is the root of all evil

Your reverence is going to weed;

It's the work of a saint, not a

sinner,

To shake your clothes out for

seed.

When

Russell's depictions of the Wild West depart from the heroic white

Westerner to the criminal element, the deviation is also one from the

sublime to the ridiculous, for the painter almost always depicts the

cowboy or the sheriff or the soldier as an exalted hero, while he

portrays the outlaw as an absurd buffoon. The True West, he implies,

is about the men who tamed the wilderness and civilized the frontier;

it is not about those who, like robbers, attempted to subvert law and

order, nor is it about those who, like Native Americans, fought

against or stood in the way of progress.

Russell's

paintings show rugged Western terrain, its plains and mountains,

canyons and gorges, deserts and snowy highlands, rivers and lakes,

pines and cacti. The landscapes also depict the wildlife of the West:

buffalo, mustangs, wolves, bears, big horn sheep, elk, and deer. Such

paintings reflect the reality, in the untamed West, of the need to

“kill or be killed.” The frontier is a land “red in tooth and

claw,” in which “only the strong survive” in a constant contest

in which “the survival of the fittest” is enacted every day,

whether among plants, animals, or men.

Signs

of stable, established civilization—white civilization, that is—are

few and far between in Russell's oeuvre: an occasional cabin,

a trading post, a saloon, a fort, storefronts along a boardwalk

adjacent to false-fronted buildings built mostly of wood. Only rarely

is there a brick or stone edifice suggesting commitment and

permanence. Most of the signs of white civilization, the foil of

which, in Russell's art, is the nomadic culture of the Native

American, as represented by temporary camps of tepees and clothing of

blankets, loincloths, beads, moccasins, robes, and headdresses,

buckskin dresses or skirts, and coarse blouses, are transient: chuck

wagons, buckboards, stagecoaches, trains.

Russell's

vision of the West is flawed. Stereotypical at best, it borders upon

racism at times in its depiction of white men as the rowdy, uncouth

bringers of civilization to the untamed West and of Native Americans

as typically (that is, stereotypically) savage and militant,

uncivilized and hostile, wild and brutal. White men have come to tame

the West, and that includes the savage, uncivilized Native Americans

who attack the newcomers' camps, settlers' cabins, wagon trains, and

railroad cars. For the West to be tamed, the Native American must be

defeated, killed, banished, and otherwise controlled. These ideas are

implicit in Russell's art. It is politically incorrect.

There

is, however, truth in his depictions of Native Americans as well as

implicit falsehoods or misrepresentations. The cowboy, the farmer,

the rancher, the sheriff, the railroad worker, the miner, the

soldier, and the other white figures of the West did bring

civilization—their

civilization—to the West. They built towns. Schools. Churches.

Telegraph lines. Railroads. Stockyards. Gold and silver mines.

Russell's

heroes built cabins and houses and towns on plains. They laid rails

so that trains could travel over mountains, bridge canyons and

gorges, and cross miles of desert wasteland. Their boats journeyed up

and down rivers and across lakes. They built houses from oaks and

pines and quenched their thirst on the juices of cacti. They hunted

buffalo, elk, and deer. They captured and domesticated mustangs. They

killed dangerous wolves and bears. They made the West habitable and

safe—or safer, at least, than it had ever been.

Eventually,

they, or their children, also built newspaper offices, libraries,

museums, art galleries, department stores, and a host of other

pedagogical, religious, commercial, technological, journalistic, and

artistic institutions; they spread Western culture throughout the New

World. In that sense, the Western heroes Russell's art depicts were

heroic, indeed; they were larger than life; they were knights in

Stetsons and gun belts and boots.

Despite

Russell's lopsided and oversimplified view of Nature and Civilization

and their respective human masters, the Native American and the

mostly white Westerner, the painter constructed a vast, panoramic

vision of this conquest of the Wild West that continues to have a

powerful effect on the imagination and the emotions. It is a vision

which, although in need of correction and further development, is one

that can still be considered inspirational to a significant degree.