Copyright 2020 by Gary L. Pullman

In

the April 11, 1895, supplement to the Barton County Democrat,

which was published in Great Bend, Kansas, the anonymous author of a

“Good Humor” column concerning “The Philosophy of Happiness

Under All Occasions” treats his readers to a treatise on the topic

of humor's frequent origin in unpleasant experiences.

Burke and Goldsmith

The

article starts the ball rolling by recalling that Oliver Goldsmith

(1728-1774) once observed that it was "the unhappy lot" of [Edmund] Burke (1729-1797) 'to eat

mutton cold and cut blocks with a razor.'” (Like most Western

newspaper articles, this one seeks to enrich its readers' vocabulary,

offering them such rarely employed words as “anteprandial,”

meaning “prior to eating a meal”; “prandial,” which means “of

or pertaining to a meal”; and “haec fabula docet,” meaning

“this fable teaches us.” Whether the journalist's purpose is

pedantic or pedagogical is, perhaps, like the madness of many an

Edgar Allan Poe protagonist, insusceptible to analysis.)

We

are to learn, however, from Burke's “unhappy lot” that

experiences which seem bitter during their occurrence can later prove

to be fodder for amusement—that of others, if not our own. The

“cold mutton” and the “blocks,” although unpleasant in the

eating and in the cutting, respectively, nevertheless may later

occasion humorous treatment. (Many stand-up comics echo this

observation, declaring that calamity and catastrophe, especially of

the personal variety, often bear the fruit of laughter.)

We

are next advised that Joseph Addison (1672-1719)—the “Good Humor”

columnist, either because of space limits or to impress his readers

(or himself) concerning his intimacy with the authors whose names he

bandies about, frequently uses only their surnames—divides humor

into two classifications: “true” humor and “false humor.” The

former involves “truth,” “good sense,” “wit” and “mirth.”

(The columnist does not indicate whether it is truth, good sense, or

wit and mirth that makes “true humor” true, but seems to suggest

that true humor is derived from, or based upon, all these

ingredients.) False humor is predicated upon “nonsense,”

“frenzy,” and “laughter.”

Irving

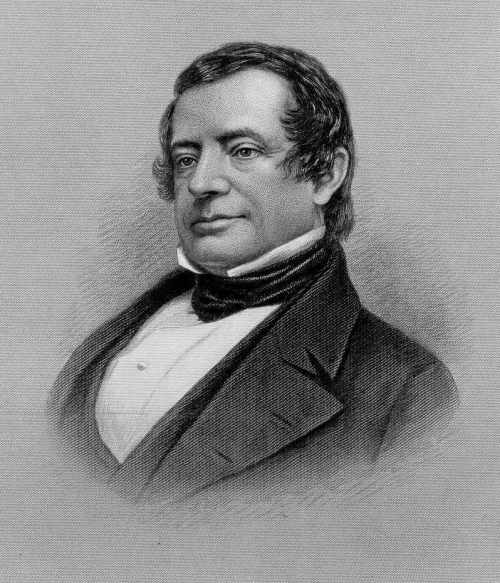

Next,

the writer references “two other great humorists,” this time,

perhaps to reveal the fact that he is not on as intimate terms with

them as he is with the others whose names he has dropped with

abandon, naming their full names: Washington Irving (1783-1859) and John Bunyan (1628-1688).

Bunyan

Neither

of these “other great humorists” is very helpful, as the comments

of both are so general as to be vacuous, Irving defining “honest

good humor” as “the oil and wine of a merry meeting,” adding,

with no more clarity, that “no jovial companionship [is] equal to

that where the jokes are rather small and the laughter abundant,”

despite his own earlier comparison of “honest good humor” with “

the oil and wine of a merry meeting.” Bunyan prefers poetry to

prose, offering this obscure couplet: “Some things are of that

nature as to make/ One's fancy chuckle while his heart doth ache.”

The

article ends where it began: nowhere. Despite the aid of Goldsmith,

Burke, Addison, Irving, and Bunyan, we learn virtually nothing about

humor and less about wit, although our guide has insisted that “good

humor is a great constituent in happiness in life,” while warning

us that “wit, unless it is of the kindly sort” (in which case, it

is not wit, after all, but a species of “good humor”) “may be

valuable in giving a sense of intellectual supremacy” to those of

us, presumably, who are troubled by poor self-esteem or who imagine

ourselves as being intellectually inferior to others. Since wit

“never makes friends,” the journalist assures us, we are “better

off without it,” if we want to live a happy life. (Why, then, does

the writer bring it up at all? To reach the allotted word count for

his column, I suspect.)

The

whole point of the column is to explain how we can, through the

exercise of humor, live happily ever after, but the column does

almost nothing to help us understand what humor is or how to employ

it to this (or any other) purpose. However, in reading the column, we

might have been entertained, if not amused, for a few minutes, and we

might suppose that we had learned something worthwhile. We might even

believe that we now have the secret of happiness for which humanity

has longed since the days of our

primeval parents.

No comments:

Post a Comment